Illustrating The Crisis: Pt 1

- Valerie Harris

- May 28, 2024

- 4 min read

Laura Wheeler Waring’s long career as an illustrator for The Crisis magazine

picked up steam in the fall of 1917. The “Great War” was on the minds of black Americans and was often depicted in The Crisis as a means to emphasize the hypocrisy of the U.S. government in sending black soldiers to Europe to kill the enemies of democracy while allowing white soldiers and others to terrorize and kill black citizens at home.

Particularly noteworthy were the deadly East St. Louis riots that took place in Illinois in the spring and summer of 1917. White mobs attacked black residents, ambushing African Americans on their way home from work and destroying their homes and businesses. Still, the magazine encouraged the race to support the war effort, partly through war-related drawings of Negro soldiers provided by male contributing artists Lorenzo Harris, working out of Philadelphia, Indianapolis-based painter, William Eduoard Scott and Chicago painter, William M. Farrow.

The Crisis portrayed black soldiers as patriotic and brave, and black women as supportive and faithfully awaiting the return of their men.

This sentiment was one that Laura Wheeler could lend pen and ink to.

It is likely due to writer, Jessie Fauset’s influence that Laura was tapped to illustrate the poem that appeared in the September 1917 issue—the beginning of what would be many collaborations between the two women.

“Again It Is September” carried the byline, “By Jessie Fauset With A Drawing by Laura Wheeler,” giving text and image equal weight. The protagonist of Jessie’s poem offers “a sigh of deepest yearning…” and reminisces of “kisses wild and burning…” as she sits “mutely praying” that she “may not remember!” Laura’s illustration depicts a young woman of indeterminate race--"neither white nor black"--sitting on an ornate bench in a garden setting, an open book in her lap, musing, her mood as languid and dreamy as the flowing floor-length gown she wears. In their writing and art, Laura and Jessie managed to present a discrete transition from the horrors of East St. Louis to the pervasive loneliness of those left behind as their men went off to war. Their collaboration upheld the upper-class woman’s conventional role of…waiting.

In reality, it was a role that neither Jessie nor Laura played very well when it came to pursuing their creative and professional goals.

The poem appeared within the pages of The Crisis after a long feature on the East St. Louis massacre and another story on the silent vigil of hundreds of black men, women, and children, marching from 57th Street in New York City to Madison Square in protest of the recent outrages. Jessie and Laura’s collaboration made the “Great War” seem romantic, almost genteel in comparison.

Throughout her tenure with The Crisis, Laura Wheeler Waring contributed very few illustrations that conveyed a political perspective. One exception appeared in November 1917— “the Suffrage Number.”

Women’s right to vote was a hotly contested issue within the black community. Black scholars frequently wrote and spoke out against woman’s suffrage, asserting that giving women the right to vote would jeopardize the rights of black men. The Crisis editor, W.E.B. DuBois was decidedly on the pro side. An unsigned editorial--presumably by DuBois--urged New York’s 75,000 black male voters to go to the polls and grant the vote to women in that state, and for Negro voters across the country to do the same at the earliest opportunity.

The Crisis’ educated, middle-class readers were reminded that “the day when women can be considered as the mere appendages of men, dependent upon their bounty and educated chiefly for their pleasure has gone by.” The editorial further noted that in the south, “while you can still bribe some pauperized Negro laborers at election time you cannot bribe Negro women.”

But black women were catching it from both sides. Prominent white women—unwilling to lose the support of their southern sisters—frequently spoke out against granting the vote to black women. The Crisis editorial went on to state: “We cannot punish the insolence of certain classes of American white women or correct their ridiculous fears by denying them their undoubted rights.”

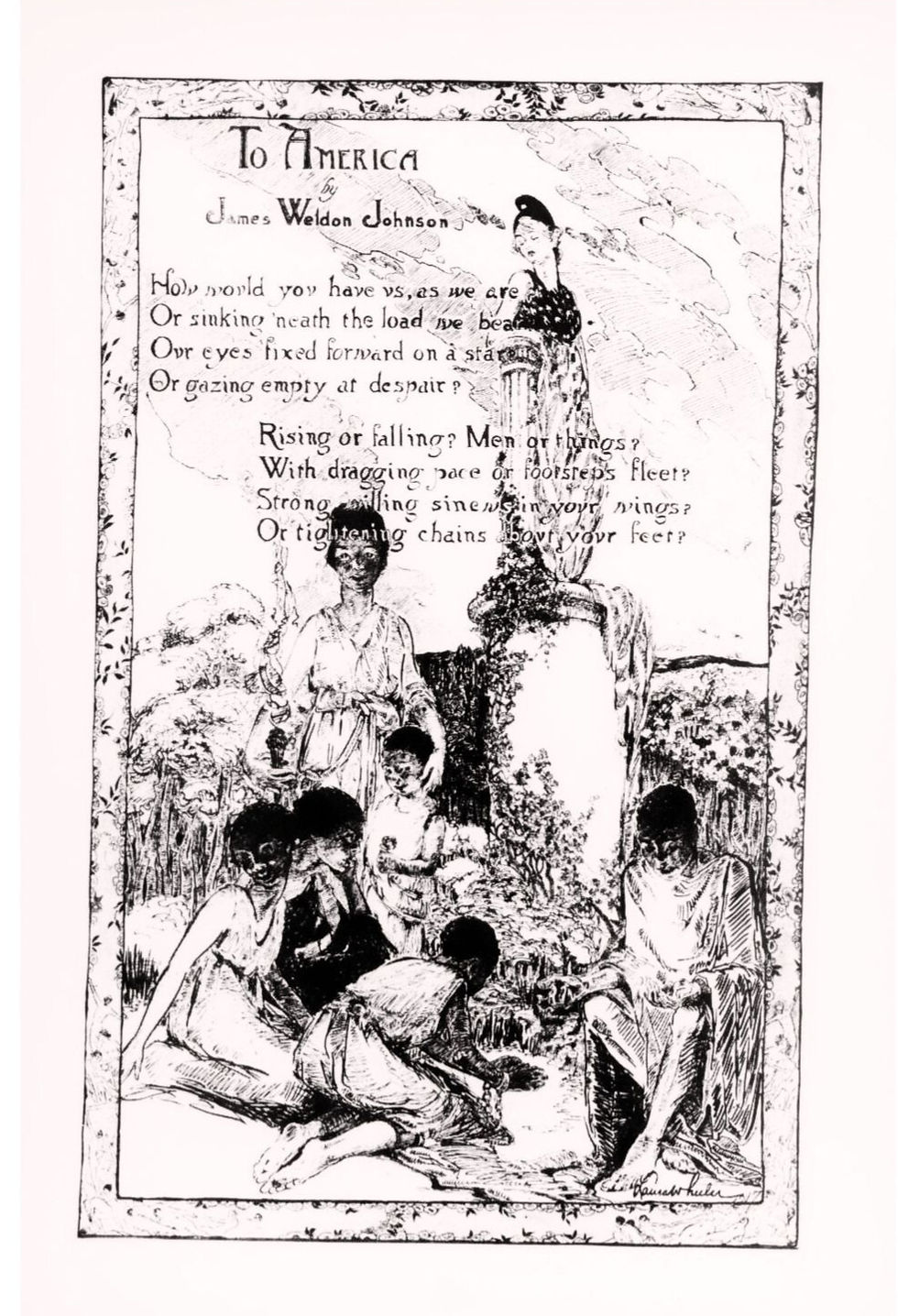

The Crisis’ issue devoted to universal suffrage featured a poem by writer and NAACP Field Secretary, James Weldon Johnson entitled, “To America.” Perhaps Johnson spoke to white Americans on behalf of black women as well as the race as a whole in the poem’s opening lines:

“How would you have us, as we are?

Or sinking ‘neath the load we bear

Our eyes fixed forward on a star

Or gazing empty at despair?”

To illustrate Weldon’s poem—and perhaps to make her own statement on the downside of women’s suffrage as it pertained to black/white relations—Laura depicts a white woman draped in an American flag standing atop a pedestal. The woman looks disdainfully down on a woman of color who stands below, protectively shepherding a group of black children.

The black woman and youth are draped in plain white shifts, the children kneeling or sitting, one with hands outstretched, another clearly bound and hampered by chains at the wrists, unable to drink from the pool.

In this instance, Laura used her illustrative skills and her calling as a teacher to convey that white America oversees and hinders black children from partaking of the sacred water of intellectual enlightenment and equality.

© 2023-2026 Valerie Harris. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Comments